About Me

|

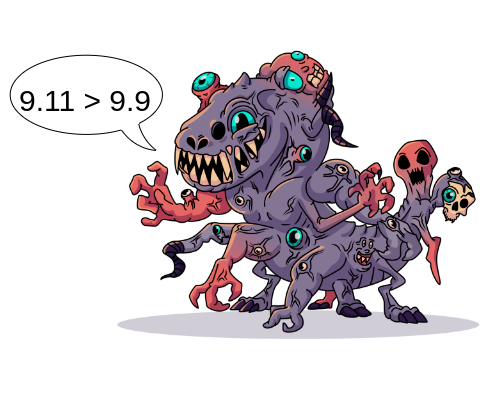

In these exciting times, self-driving cars are taxis, robots are chefs, and large-language models assist coders, lawyers, and medical professionals alike. This is possible because of amazing progress in large-scale deep neural networks. However, today's large networks have known limitations [1,2,3,4]. Training with GPUs is expensive and meaningfully contributes to climate change [1], our responsibility to ensure data privacy restricts access to important data sources, the interpretability of deep features is lacking [2], and deep networks learn superficially [3]. Perhaps the most pressing outcome culminating from these problems are unpredictable failures and untrustworthy results [1,2,3]. These issues inspire analogies between large-scale deep neural networks and fictional creatures such as Mistwraiths and Shoggoth. Mistwraiths use bones of other creatures to construct their own skeleton. They do not care if there are three skulls instead of one, how many arms they have, nor if there is a hand among their feet. All that matters is that they “usually work”. However, this concept of “usually working” is limited by the extent of our testing, which is problematic for the heavy-tails of a real-world settings. Improving large-scale networks one bug at a time is like chasing infinity. So what can we do to reliably use the power of deep neural networks? |

|

My purpose for studying computer vision is to serve as a sensor for automous systems. I love the idea of AI acting in the physical world, and I find it exciting we live in a world where self-driving cars exist. I would love to work on the algorithms for the feasible and safe commercialization of a home robot in the truest Jetson form. While this long-term goal will take many decades of focused research across many disciplines, I believe a core aspect of the solution will include specialized deep neural network modules using inductive bias. Currently, I live in West Lafayette, Indiana, USA. I was raised in Indianapolis, Indiana. I am the youngest of three kids. My sister and brother live in Chicago, Illinois. My parents still live in my childhood home back in Indianapolis. Mohana, Captain America, and Frozen are great movies. I enjoy running long distances when I am not injured. I enjoy reading and coding. I love how people are using machine learning to be creative, with one example being CMLR. |

References

Wu, Carole-Jean, et al. “Sustainable ai: Environmental implications, challenges and opportunities.” Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 4 (2022): 795-813.

Bommasani, Rishi, et al. “On the opportunities and risks of foundation models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258 (2021).

Geirhos, Robert, et al. “Shortcut learning in deep neural networks.” Nature Machine Intelligence 2.11 (2020): 665-673.

Dziri, Nouha, et al. “Faith and fate: Limits of transformers on compositionality.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

Bronstein, Michael M., et al. “Geometric deep learning: Grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.13478 (2021).

E. Bekkers, An introduction to group equivariant deep learning. Available online: https:uvagedl.github.io

Cohen, Taco S., and Max Welling. “Steerable CNNs.” International Conference on Learning Representations. 2022.

Freeman, William T., and Edward H. Adelson. “The design and use of steerable filters.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern analysis and machine intelligence 13.9 (1991): 891-906.

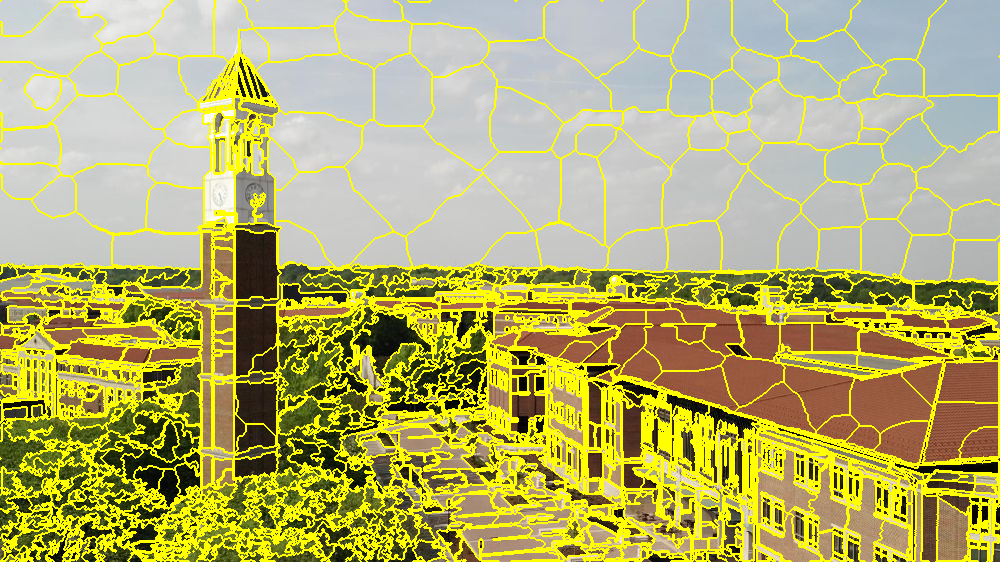

Ren, and Malik. “Learning a classification model for segmentation.” Proceedings ninth IEEE international conference on computer vision. IEEE, 2003.